#09: On Towers, High-Rise and Vertical Constructions

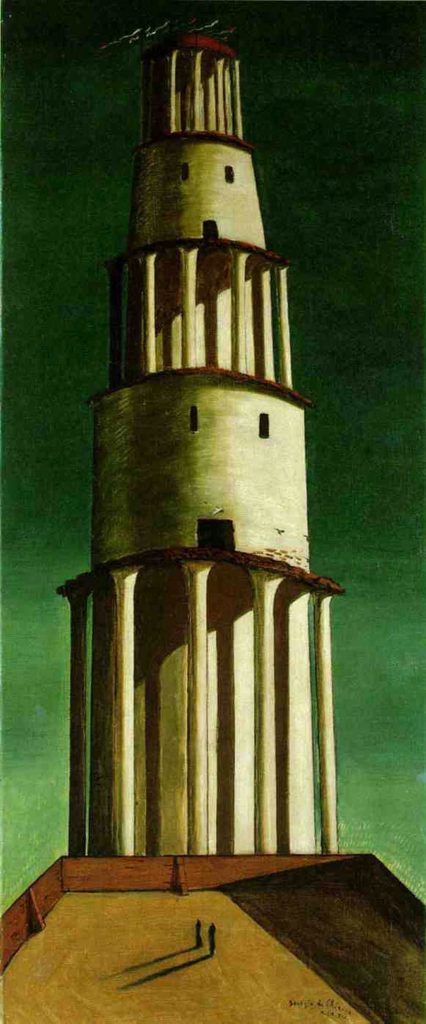

Since ancient times people have been building towers as an act of unifying the earthly and the celestial. Ziggurats, pyramids and stupas (all massive stone structures used for religious purposes) represent the image of the cosmic mountain standing at the centre of the world, functioning as a mediator between humans and the gods. One of the most well-known (biblical) towers is the Tower of Babel, as depicted by Pieter Brueghel the Elder. The vertical ambition of humans to build a tower that will reach to heaven was being obstructed by god, which confounded their speech, so that they would not be able to communicate with each other and finish the construction.

Later on, church towers and minarets were built to pierce the heavens and thereby ringing the sounds of bells and prayer, to mark sacred space and time. Towers functioned as a landmark, they worked as a beacon in the wilderness of the landscape. It is interesting to consider that until the first high-rise buildings and skyscrapers of the 19th century the towers of a church, cathedral or fortress where the highest point to be seen in a landscape.

As we can clearly see in the painting of Jacob van Ruisdael, View on Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds, the religious towers of the cathedral and churches of Haarlem function as a landmark, a vertical pinpoint in the compellingly flat and horizontal Dutch landscape. It feels like the tower was always there, always visible at any point in the city or landscape. The gothic era was about putting one’s life into the service for the greater good and making a contribution to the construction of the cathedral. The construction could last over multiple generations, and most of it’s construction workers would never see the tower being finished. In that way the towers would not only stand as the beacon in the middle of a city, but also as an absolute central point in the daily lives and imagination of the cities’ inhabitants.

Nowadays, in most European villages and cities, the church spires are still the highest buildings in the city centre. There are often heavy debates going on whether there can be a place for modern high-rise in historical city centres. The apartment building at IJdock, Amsterdam from Zeinstra-Van Gelderen architects (2013) is an interesting example of the clash between the old historical city centre and the modern architects with their vertical architectural ambitions.

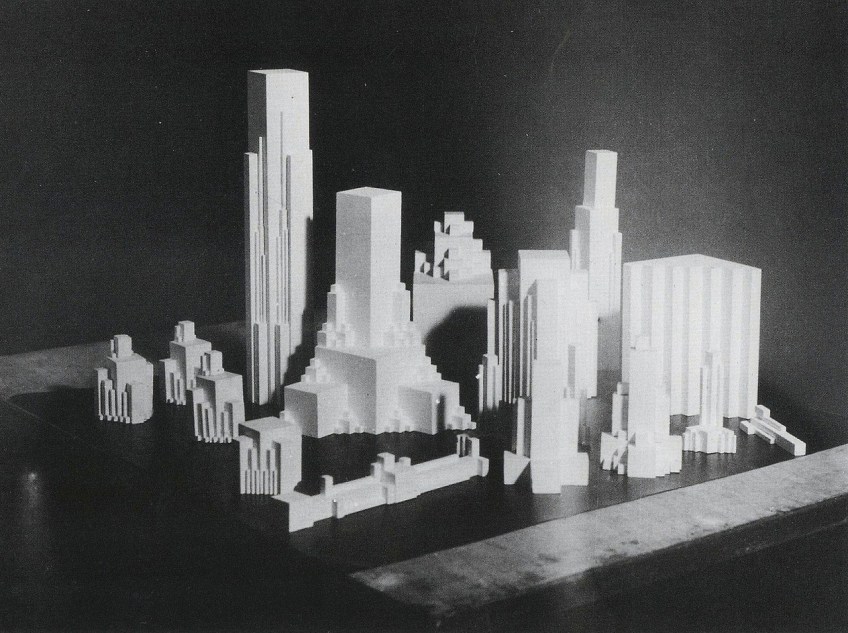

With its position between het IJ and the city centre, IJdock was very attractive for project developers. Different from Rotterdam, in Amsterdam everything which is higher than a church spire is suspicious. When the IJdock was initiated, the plans were rejected by different kinds of organisations who wanted to protect the historical sightlines and the 17th century skyline. The horizon of the historical city centre should not be ‘polluted’ by modern high-rise. The solution to this problem was to cut an enormous shape out of the scale model in the exact same form as the historical sightline as seen from the canals. In this way the building was molded to the view from the canals on Het IJ. I can imagine how a large part of the scale model was just being cut away from it’s original form, leaving a V-shape behind. Thus the high-rise building of IJdock almost functions as a window, a ‘negative’ framework around a historical sightline.

Another interesting example of building upwards was one that I found while traveling in Morocco a few weeks ago. In the rural areas of the country all houses and buildings were built in the exact same way. Over here we can see a type of housing which is completely standardized and not directly planned by any architect. A simple method of a reinforced concrete construction, filled up with walls of breeze blocks and red plaster work in the same color as the house surroundings.

What was interesting to see is that, for an outsider, it was not clear whether the house was still being built or was already abandoned. Many structures and buildings were in this ‘in-between’ state; somewhere between being constructed and being finished. The steel wires sticking out of the concrete structure suggest that a new floor can be added to the existing building. It might be that the inhabitants ran out of money during the construction, and some floors of the house would remain unfinished. When after a while the inhabitants had more income, they could add an extra floor to their house. It might be interesting to see how buildings in this area grow taller and taller over time. I can imagine towers growing out of houses when more money is being earned.

The housing structure in Morocco is based on a much older construction principle initiated by the French architect and urban planner Le Corbusier. Out of an urgent need of housing after the First World War, the architect came with the idea of the Dom-ino (from the Latin ‘dooms’, which means ‘house’ and an abbreviation of ‘innovation’), which would mean something as innovative house. The Dom-ino was a simple construction which could be prefabricated and repeated over and over again, all over the world. The different Dom-ino constructions could also be variated and connected to each other in all different kind of forms, like the stones in a domino game.

Although the idea of the Dom-ino was initially meant for the scale of a house, later on the construction principles would return in Le Corbusier’s high-rise towering architecture of the Ville Radieuse. A strong reinforced concrete structure would carry the floor, so that walls and facades would no longer have a constructive function. Thus, the floor plan and the facade could be freely designed, in order to make room for large horizontal windows, so that the rooms could bathe in daylight. Nowadays we can still find the ideas of the Dom-ino construction in the buildings around us. For example in the building of the former Hogeschool at Nijenoord, Utrecht. What is interesting to see is how the whole building is being stripped back to it’s origins. The facade of the building is peeled off, so that a new design can be made and being placed back onto the building again. The whole school building is being transformed into a residential property. In fact, the building stays the same but can be rearranged to the needs of a certain time. A building as a tabula rasa, an empty shell, to which function and identity can be assigned.

If you are interested in the outcome of the research, and the new work I have made in De Torenkamer, check out the website of Opium op 4.

Bart Lunenburg (1995) graduated with honours from the Utrecht School of the Arts in 2017. His graduation project, Doorzon, is about how we relate to our daily environment. He researched the meaning and role of the window in architecture, visual arts and photography, using his direct surroundings as a starting point. Observations in his neighbourhood form the basis for scale models and interventions.

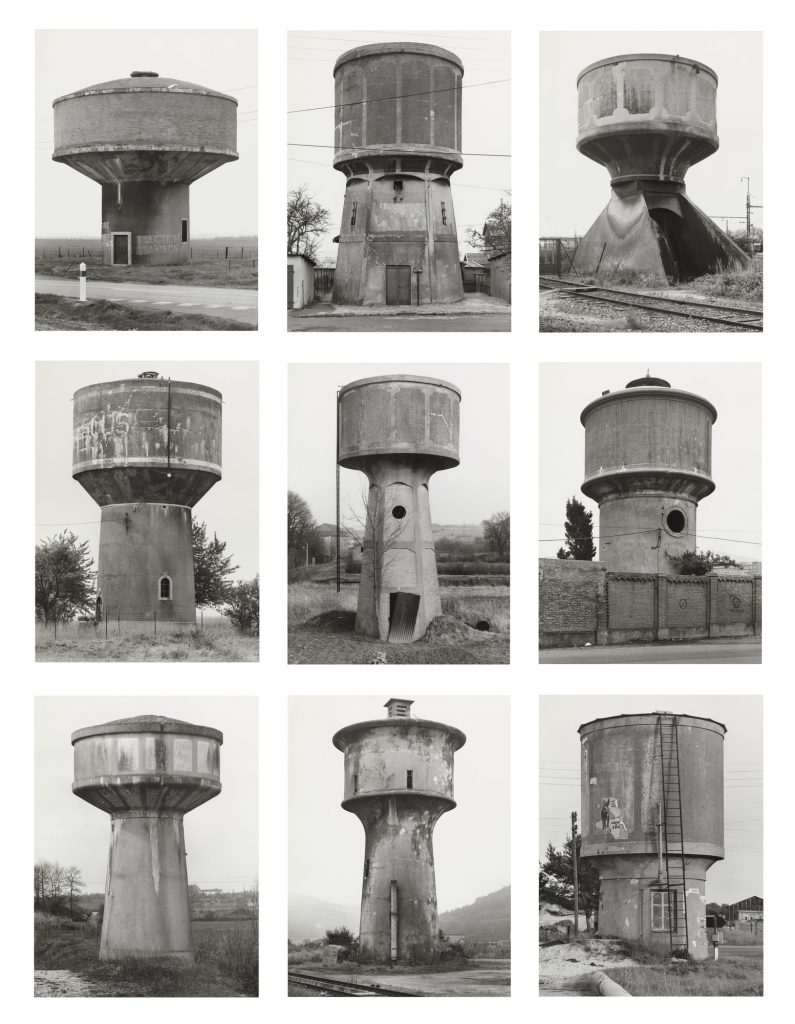

This week I am preparing myself for a short artist-in-residence at De Torenkamer provided by the radio program Opium op 4. During this residency I will be researching different sorts of towers, both in the history of art and architecture, as well as in our daily lives. This research will lead to the making of new scale models, which may lead to new photographs, video works or sculptures. For Outlines’ Anything Makes Sense I would like to give a small insight into my research process.