#11: Fragility within and around the archive

This e-log shows you…

My thoughts and stutters when encountering a postcolonial confrontation in curatorial practices.

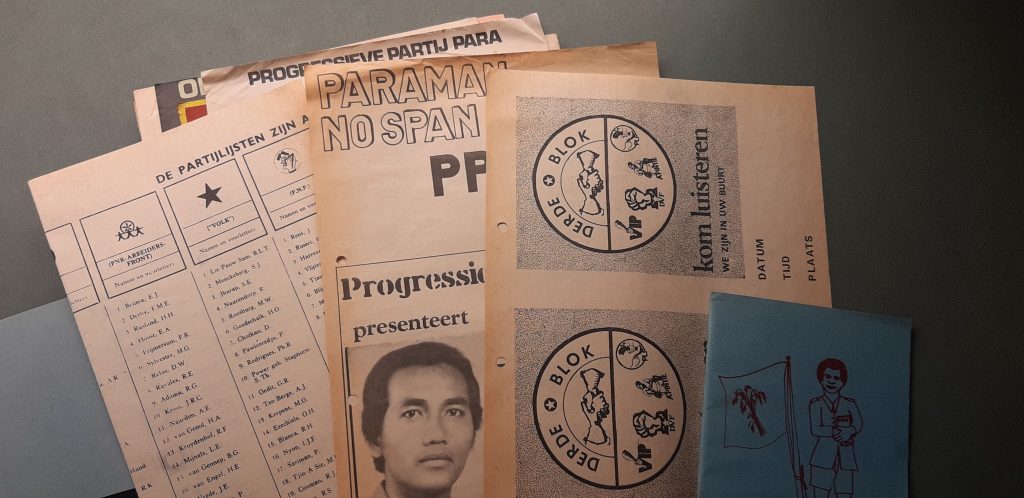

I will share with you a selection of archival documents that have been stored by the International Institute of Social History1 in Amsterdam. Together, these papers, photos, sounds and 16mm film prints represent the history of the activist film production Oema foe Sranan/Women of Suriname, a collaborative production made by the Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms collective and LOSON (National Organisation of Surinamese in the Netherlands). Cineclub was an activist film collective that worked as a producer, distributor and exhibitor of political and subversive films from 1966 until 1986 in the Netherlands. LOSON was founded in 1973 by a group of Surinamese students who were critical of the American and Dutch (neo-)colonial affairs of exploitation in Suriname and as such they supported the workers’ and independence movement in Suriname whilst studying in the Netherlands. They advocated for the social progress of Surinamese migrants in the Netherlands and emphasized the importance of solidarity between Surinamese and Dutch.

For almost two years now, I have been taking snippets from the Cineclub collection, dragging them into documents (articles, a MA thesis, fund applications) and into presentations, cinema rooms and conversations with friends. I exercised my academic and curatorial power over these documents by interpreting them, as a means of restituting them in front of old and new audiences and in between old and new topics of debate. The local militant history of film, and the way in which Cineclub developed a network at the intersections of politics and film in Amsterdam is something which I aspired to reconstruct. In this text I will disclose not only a part of that archival exploration, I will also try to disclose my position within this historical research.

Levels of disclosure

Disclosing a collection occurs at a technical level as well as as an imaginative level. On a sensory level I noticed:

The size: an 11.5 meter long paper archive;

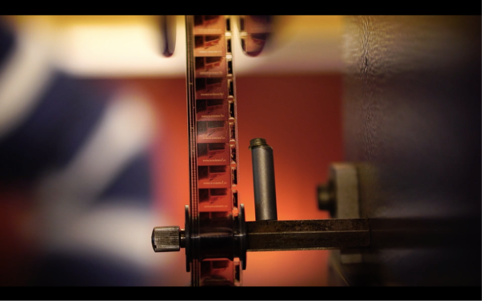

The smell: of vinegar in film, of rusty cans, of sweet and musky paper;

The (lack of) colour: paper turned yellow, analogue film turned red;

The gloves: the delicacy with which one should go about in touching spliced, moulded or scratched 16mm prints;

The recognition of hand writings;

The chaos that’s behind all these well-ordered, categorized boxes.

Oema onto the silver screen

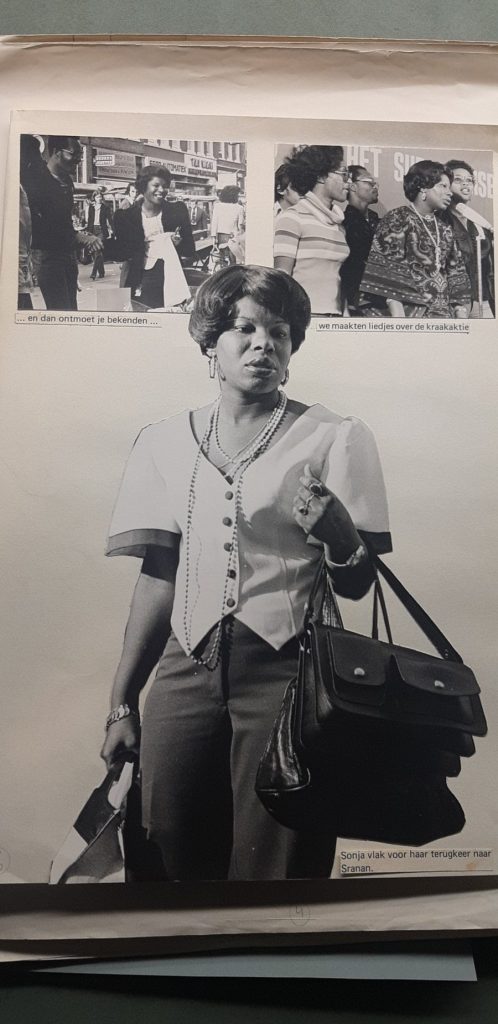

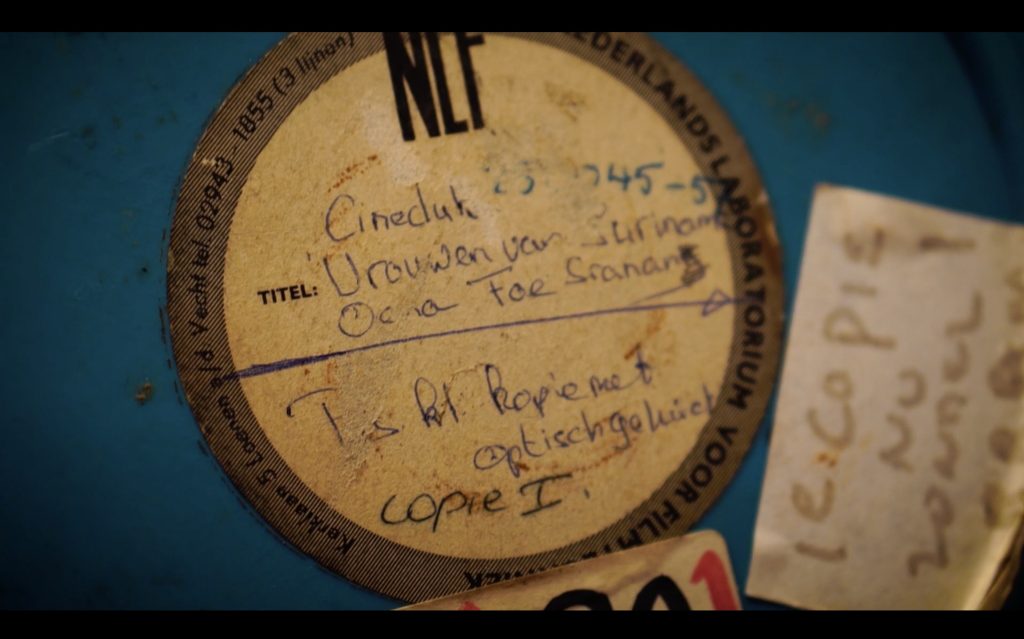

Yes, this unstudied archive evoked a certain attraction. Researching this 16mm film collection with my fellow film programmer Luisa González, we inevitably made a jump from the archive of attraction to the ‘cinema of attraction’2. Oema foe Sranan/Vrouwen van Suriname/Women of Suriname, a film shot in the context of the independence that Suriname gained from the Netherlands in 19753. An auto-ethnography: a film that portrays the life of Sonja, Sylvie, Somai, Jetty, through which a history of Dutch colonialism, neo-colonialism and discrimination in Suriname and The Netherlands is captured on a fragile, discoloured 16mm print that awaited us in one of the rusty cans.

Combative fires

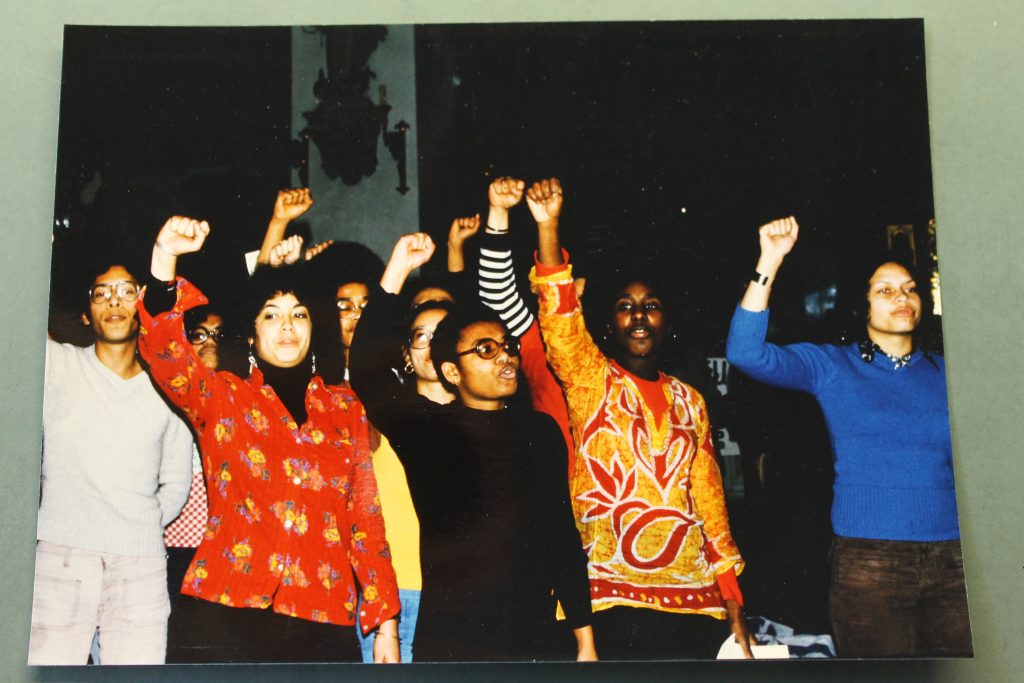

A happy coincidence led us to the living and breathing bodies which the archive couldn’t carry: those who created this history. They are the now sixty to seventy year old ex-LOSON activists that partially produced4, edited, wrote and distributed Oema foe Sranan together with Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms in the 1970s and 1980s. We got acquainted with their combative fires, some of them more pronounced than others. Confronted with the way that I listened to their socialist vocabulary – comrades, solidarity, collective, union – realising how the neo-liberalism in which I was raised crushed the credibility of these terms and initially set them away as old-fashioned. The encounter with a forgotten vocabulary and a forgotten film style (that of militant, collective filmmaking) drove me to continue discussing and researching their history. I was confronted with the relevance of this vocabulary, or perhaps with the urgency of recreating a vocabulary that applies to the struggle of a new generation.

A curator’s stutter

Starting from a sensory sensation and fascination for the unopened film cans we ended up with an overwhelming and sometimes confusing oral history that took shape during our preparations for the screening of Oema foe Sranan in Filmtheater Kriterion in Amsterdam. At the night of the screening a panel discussion with Henk Lalji (filmmaker), Nadia Tilon (narrator and music supervisor), Juanita Lalji (distributor), Ditter Blom (LOSON’s secretary) and I took place. During this session I was confronted with a situation in which I needed to legitimize my interest in Oema foe Sranan in an unexpected fashion. During the discussion that was concerned with both the history as well as the current situation of Suriname, the moderator, Ditter Blom, genuinely asked me what I, given my Dutch background, thought of the film. I was overwhelmed by his question; I had expected an inquiry about my archival expertise or historical knowledge on the collection from which this film derives. The thing with which I was confronted the most, as Ditter and other audience members asked me about my personal views on the film, was that I never considered my own position-taking. It was an undiscovered history, it was the unopened files, the untold stories, the excavated emotions of others, these things were my justification in working towards the disclosing of this film and its history.

The identity politics of fear

Being surrounded by a mainly Surinamese-Dutch crowd, I felt a fear overwhelm me: the fear of saying something inappropriate as a white and Dutch-born curator. I felt stuck in the position of a researcher that thought could elevate herself from personal interest and feelings; I was there to reconstruct facts, not feelings. I mumbled about how the images fascinated me, and how I recognized parts of Surinamese-Dutch culture that I got acquainted with in the Netherlands. I mentioned something about the urgency of restoring this heritage. I heard my distanced formulations amplified through the microphone, realising how my answers fitted into the academic imperialist tradition.

Whilst explaining myself I lowered my voice, until I cut myself off apologetically by saying that I was “wandering off”. In a reaction to my stammering, someone in the audience exclaimed that “these images did not fascinate him, but angered him.” His statement echoed through my head in the days after the talk. (Exclusionary and repressive) questions of identity were on my mind.

Conclusion: Curator’s positionalities

As a curator/as a historian you pick, you choose, just like an archive that decides to store this but not that, the archivist entering selects this and not that. The archival turn has made us focus on what shelters our historical documents: the arkheion5, and how these documents were gathered. By sharing with you my curator’s stutter, I wanted to point out how perhaps the contemporary terrain of politics & identity has added another layer to this archival turn: study yourself, your personal archive, before you study another. After this public stutter I fell into a process of echoing: what was my position on the material I so eagerly wanted to disclose? The institutional archive and the personal archive started rubbing against each other, disclosing not only an archive, but a part of myself.

Luna Hupperetz recently graduated as a MA student Curating Art and Cultures (University of Amsterdam). With her thesis on the Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms archive, she aimed to shape a recollection of the Dutch activist 16mm film distribution and screening circuit in between 1966-1986. Currently she is working on a short documentary that portrays the history of the making of the film Oema foe Sranan in light of the current restoration of the film print Oema foe Sranan executed by EYE Film Institute.

1. In opposition to the historiography that studied elites and political institutions, social history in the 1960s has shifted emphasis onto the politics of ‘ordinary’ people—especially voters and collective movements.

2. The term cinema of attractions is used when referring to the earliest stages of film history when the visual pleasure of film was more important than the narrative quality. One wants to arouse the viewer’s curiosity and surprise them. (See: Gunning, Tom. ‘The Cinema of Attraction: Early film, its spectator and the avant-garde’, 2006)

3. Suriname was colonized by the Dutch in 1667 until the year 1975, when Suriname became an independent state.

4. The scenario of the film was written by At van Praag, in collaboration with Bram Behr, the initiator of the Communist Party of Suriname (KPS), who was in good contact with the LOSON.

5. Derrida uses this ancient Greek word to define the home of the archive. For an accessible analysis of Derrida’s inaccessible text ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian’ (1995) click here.