#05: Mapping the immeasurable

I’m writing a text based on a selection of the large amount of images I collected in the past few months. All of these images are of nature, or they concern the depiction of nature. There is a paradox in these pictures that interests me; an artwork, or any other kind of image, is something human par excellence. The act of making something is a specifically human practice. However, what is depicted is something that completely contradicts this: nature, wilderness, the big unknown. The images are human interpretations, representations of the unknown. They are fabricated objects, copies of the unfabricated. I’d like to research these images and the motives to make them.

I think that making these images is a way of getting a grip on the unknown. When you do this, you need some control over it, but the images show a very human perspective on the wilderness. We often look for a reflection of ourselves in this wilderness; we want to measure the immeasurable so we can seemingly understand it, we use our own body as a tool to understand what is outside of it.

Images are also the bearers of human needs and desires. They speak of the urge to classify and divide every square meter on earth, and give all of it a name. The wilderness doesn’t ask to be named.

Many of these images – and mostly the ones which have a scientific function – are made in such a way that they hardly refer to the represented reality anymore. Take for example the drawings of plants and flowers in schools, an anatomy of a leave, something we’ll never actually see in nature.

A striking, and maybe even more interesting aspect of these scientific images, is that the makers of these images often didn’t see these objects or places in reality, but still present them as truth. We seek something of ourselves in the unknown.

Another thing to keep in mind is that all these pictures are two-dimensional. They are flat representations of something that in reality is all around you. This makes it easier to grasp it, which says something about the impossibility to make naturalistic reproductions of nature. It’s always merely an approach, and can never be close to the ‘real’ experience of walking through nature.

Claude Glass

The Claude Glass, also named “Black Mirror”, was an object used in the 18th century by painters and travellers. It is a small mirror with dark colored glass, in a slightly spherical shape. It serves as a way to look at the landscape, to make it comprehensible for humans.

Contradictory, the user of the Claude Glass has to stand with their back to the landscape. Then, one has to hold the glass in their hand in front of them. You can then see the perfectly framed image of the landscape behind you. There, in the palm of your head, lies the wilderness, to be seen in the blink of an eye. No overwhelming details, in a distance from your body which you can decide yourself. The Claude Glass was celebrated because it gives the landscape a ‘picturesque’ quality, also because of the yellow hue which characterizes landscape painting in the 18th century.

In his essay “Appreciation and the Natural Environment”, Allen Carlson justly compares the Claude Glass with the contemporary tendency to put view points on natural, touristic attractions. These view points are markings on the ground where you can stand to have the “perfect” view. Sometimes they go even one step further further, by putting a small frame in which you can put your camera, to get the perfect photograph of the perfect view. One doesn’t even have to look at the camera screen anymore, because there, in your hands, is the contemporary Claude Glass for the ideal landscape; to be seen in one instant, not too overwhelming and perfectly framed.

Maybe you can go as far as say that all images we see of nature are like looking through a Claude Glass: they are always just the reflections of a location chosen by ourselves, of which we decided the borders, adjusted the colors and probably left out some details; all that defines the wilderness is missing.

Atlas

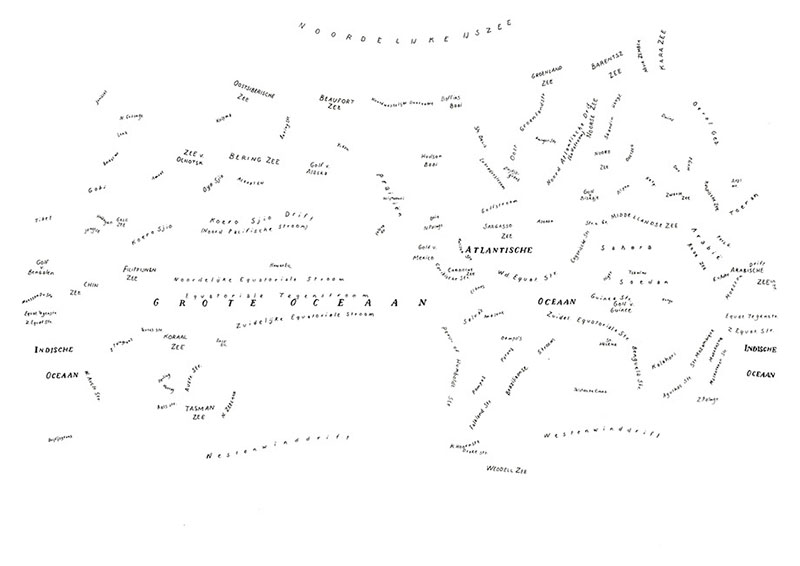

What, in my opinion, can’t be missing in a collection of images of nature are maps: an uncomplicated way of depicting what is around us, invented by us. It is a very exact way of making an image: an important difference with paintings or drawings of a landscape is that maps have a certain scientific quality. It has a clear, practical function. A landscape has to be measured and divided before a map can be made. Besides this, also contrasting with other types of images, maps also consists of language.

The language-aspect of maps played a big role in my graduation work at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. The role of language in our relationship with (unknown) environments fascinates me; how we attribute words to every area. For months on end, I was drawing my work “Atlas”, a completely written atlas, in which only language remains. While drawing, the contrast between language and space came to my attention. How some areas are too small for their name, so the names are abbreviated or the letter spacing is smaller, or how other areas are too big so the names are stretched, so it seems the letters are almost randomly scattered over the landscape. The most beautiful thing is how language can be completely formed after the landscape, and in this way gives a textual reflection of the area. It seems that the landscape imposes itself through text.

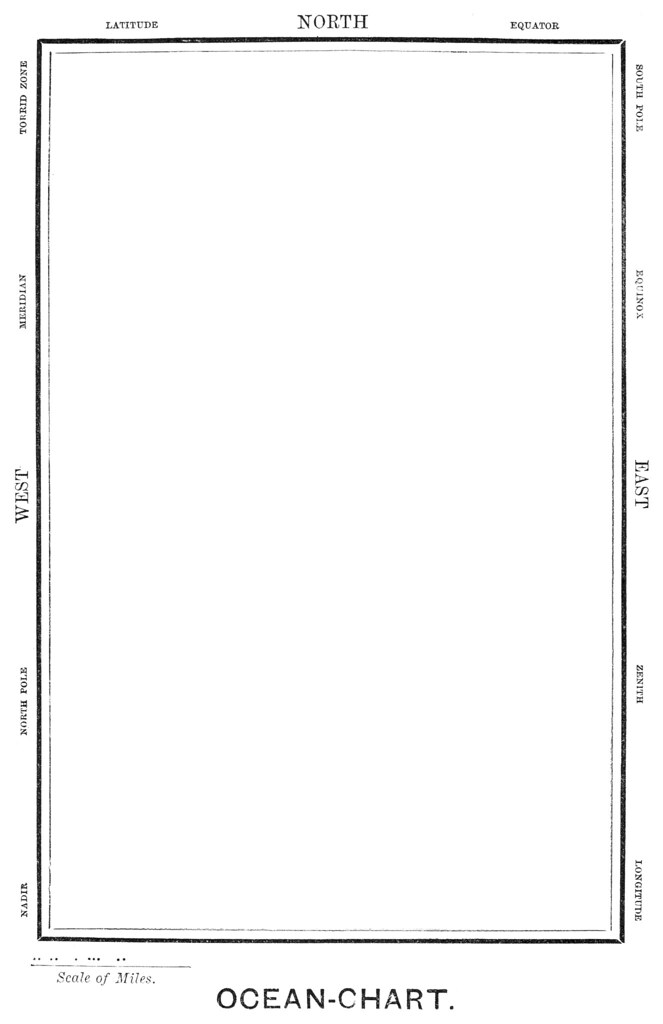

The Bellman’s map

This map, from the story “The Hunting of The Snark” by British writer Lewis Caroll, is one without colors, lines or grids. The text does remain, not in the map itself, but alongside the frame. Here we read known cartographic terms such as “equator” and “longitude”, placed in random order. But the empty spaces represented by this map aren’t random: it is the map of the ocean. This map helped in the search of the “Snark”. Although the reader immediately sees that this map has no function, the crew was very happy with it, it’s a map that everybody can understand.

“He had bought a large map representing the sea, Without the least vestige of land: And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be A map they could all understand.

“What’s the good of Mercator’s North Poles and Equators, Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?” So the Bellman would cry: and the crew would reply “They are merely conventional signs!

“Other maps are such shapes, with their islands and capes! But we’ve got our brave Captain to thank: (So the crew would protest) “that he’s bought us the best— A perfect and absolute blank!”

I think this is a very pleasant representation of the unknown wilderness, perhaps the clearest one there is: no intimidating details, nothing to worry about; there is nothing in the unknown emptiness.

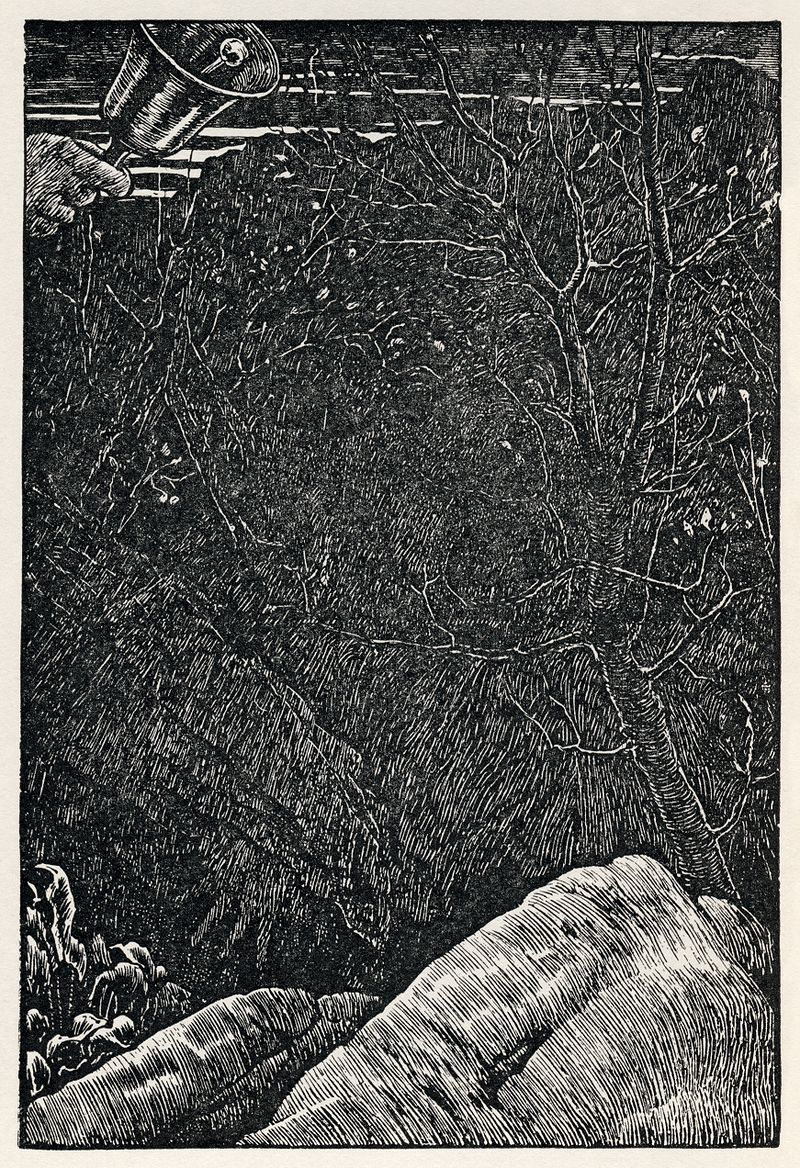

A nice detail is the very last image of the book; an almost black surface, almost the opposite of this image you see here. At the borders there are still some recognizable details: rocks, a tree, and the hand of Bellman, the leader of the journey. The image depicts the last event of the story: The Baker, one of the characters, finds the “Snark” which they were looking for, but as soon as he touches the animal, the Baker disappears. He vanishes into nothingness, into the blackness of the image (or out of it). I imagine how this disappearance might have been predictable because of the earlier map of the ocean. How, with a map of the unknown, you can only navigate deeper into the unknown, until you vanish into nothingness.

Images from ‘Depicting Antarctica’

This idea, of vanishing into nothingness, reminds me of a photograph I stumbled upon in my research on the cartography of unknown wildernesses. An example of such an unknown wilderness is the South Pole; a grand, white landscape on the lowest part of our planet, of which you know it is there, but also that you will probably never visit it.

The photograph corresponds with this feeling. On the right side you see two figures, several layers of clothing on their bodies, riding what appears to be a sled. You can also see two horses, only recognizable by the bridle and harness they are wearing, their bodies almost fade into the white background. The figures are surrounded by a large, white surface with nothing recognizable to be seen on it; no snow, no horizon, no clouds or sun. Even the shadows of the figures seem to be fading into the white. These figures are two scientists who made the first maps of the South Pole, and the grand white nothingness is this South Pole.

It’s almost as if areas can’t exist before we have divided them, as if the large white space can only get contours as soon as we decided on its borders. As if the details will only be visible as soon as we decided they are there, and what they’re called. As if the horizon can only be drawn in a right horizontal line as soon as we walked to the edges of the area, and when all the hills and depths of the landscape are calculated, divided and written down. As if it us who form the unknown, who give it the right to existence. As if the landscape is formed by the map.

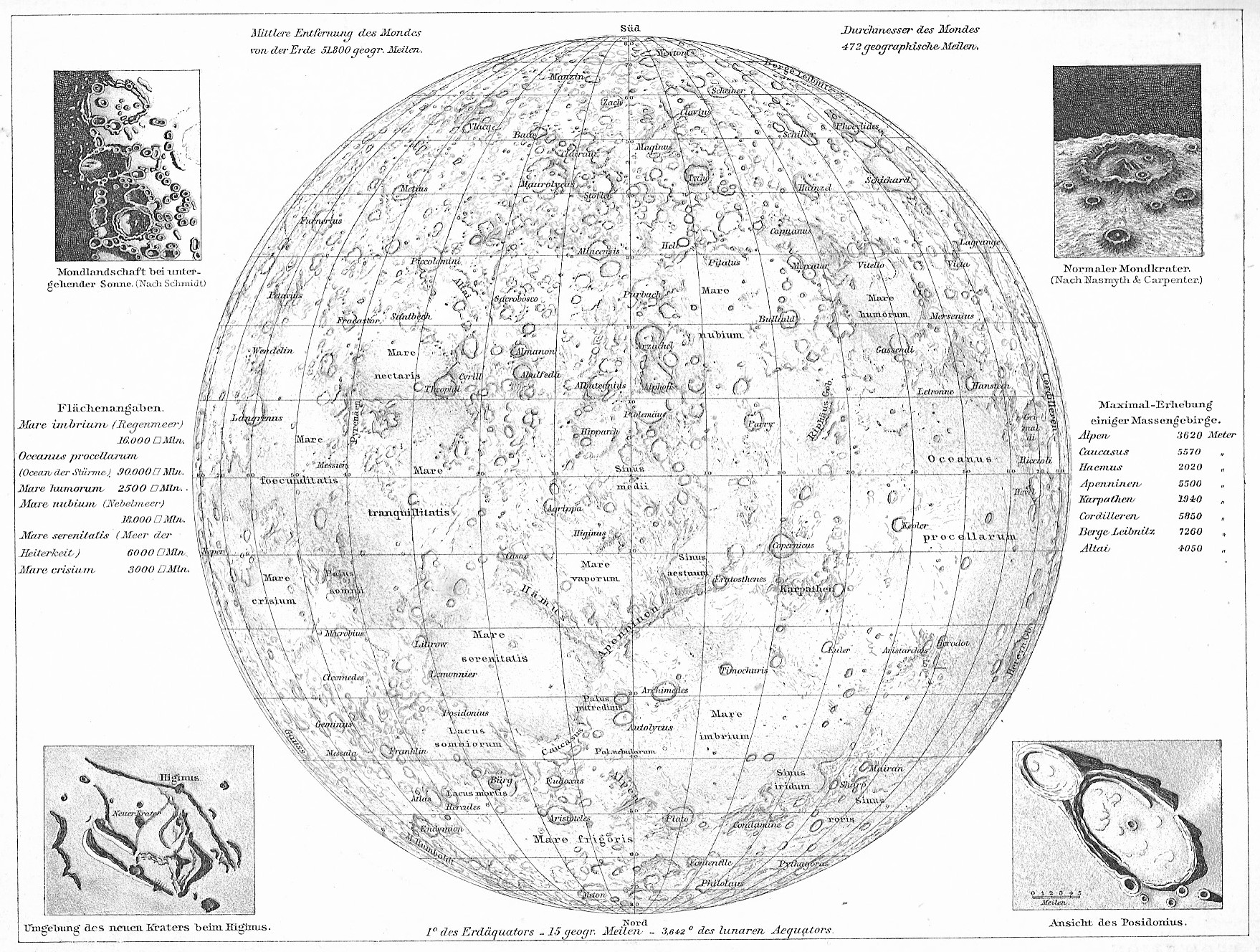

Images from ‘Mapping and Naming the Moon’

I think that, in many of the representations we make of unknown places or objects, this is the same: We ourselves play a big role in how we depict these unknown places. In the cases of paintings and drawings, this isn’t so remarkable: it’s not often that a view or landscape is exactly what we want to see, so it’s an easy choice to move a tree a little further away, or act as if there are more poppies than there really are, in a much brighter shade of red.

More interesting is how this also happens in scientific, “neutral” representations. Even if we try to be objective in our observations, the personal, human perspective on the unknown will always be noticeable. A good example of this I found in “Mapping and Naming the Moon”, a book which tells the history of images we made of the moon. The book starts with carts and images that were made before the invention of the telescope. The fact that there was a demand for a map of the moon – a place of which we didn’t even know for sure of that it was a space – tells a lot about our desire to give a name to the unknown. The first chapter talks about this phenomenon: how we constantly search for ourselves in our environment, and how our human perspective always plays a big role in the interpretation of this environment.

In the unknown we search for ourselves, for something we already know. We want to recognize something recognizable. For example, in the abstract form of the moon – a white circle with some spots here and there – we seek forms that we recognize, as if we’re doing a Rorschach test. The white circle with darker spots on this image becomes a white circle depicting a dragon, a tree and the figure of a man. These are the first names we gave the surface of the moon. An interesting addition is the role of ones own culture in the names: in China the given names are completely different; there people didn’t see a man or a tree, but a rabbit and a huge pile of rice.

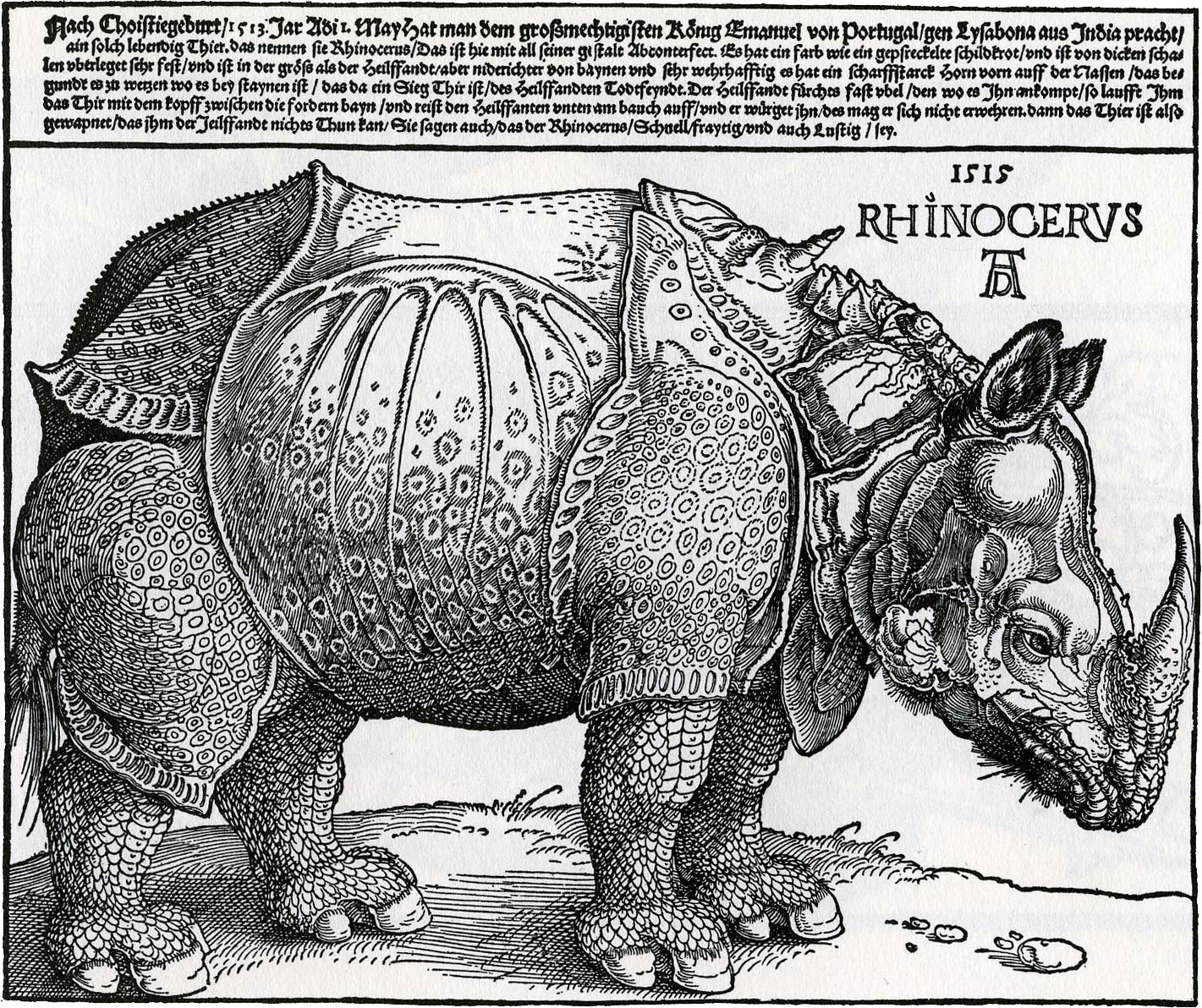

Dürer – Rhinoceros

This woodcut of a rhinoceros was made in 1515 by German artist Albrecht Dürer. It is a striking piece of work, both in the field of natural sciences and history. What, in our contemporary time, immediately catches our attention is the unnatural depiction of the rhino. The animal seems to stem from a book of fairytales: more like a rhino dressed up as a knight, chain mail and everything, than as an actual rhino. Dürer made this woodcut without ever having seen a rhino. He came to this image with the help of the descriptions of some scientists and a sketch by an unknown artist. This of course explains the odd depiction. This image was however seen as a true-to-life depiction until through halfway of the 18th century, and it was published in books and articles. Even though there are likely a lot of interesting scientific statements to make about this, it mostly fascinates me how Dürer wanted to make a true-to-life depiction of something he has never seen before, how one goes about depicting something in order to find out what it looks like. And, in addition to this, how the desire to see this image, to experience the unknown, unseen wilderness from an image, was apparently so big that people didn’t question its validity for two centuries.

Dinner in the Iguanodon Model at the Crystal Palace

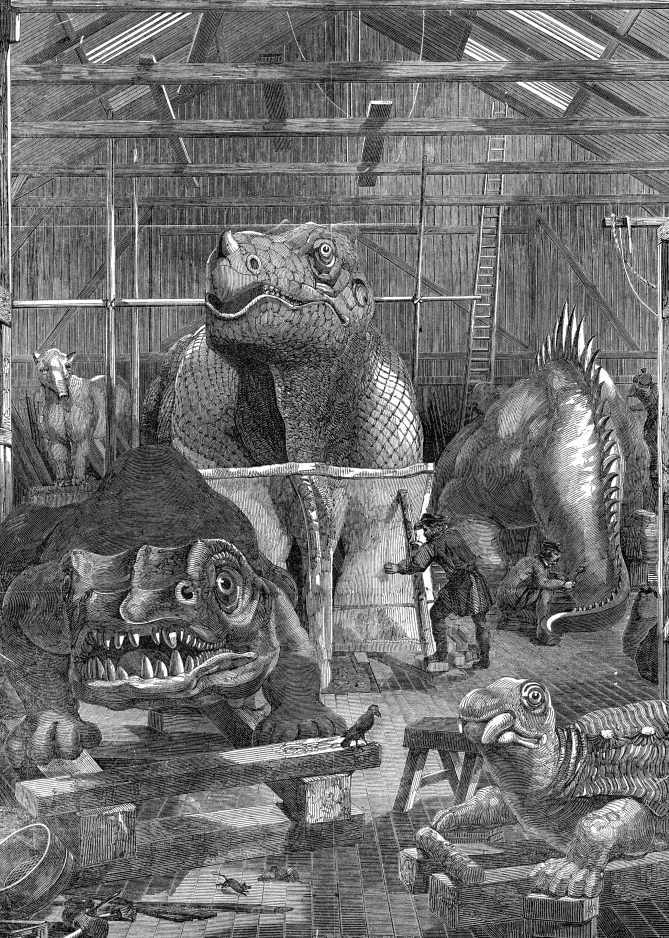

Artist working shed in Crystal Palace Park, used by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins during the construction of the famous statues

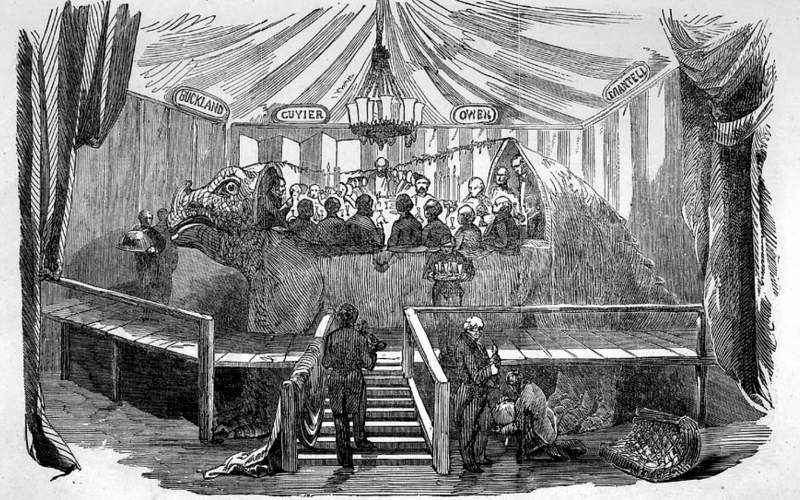

Another, perhaps even more beautiful drawing was placed in the same newspaper a week later. It depicts the so called “Iguanodon Dinner”. When the sculptures were nearly finished, they threw a dinner party for all the scientists involved. The dinner was served in the half-finished model of the Iguanodon. They placed a long table in the stomach of this beast, around which the group could sit and eat. I think this is a fantastic image: how the discoverers/authors of this animal all fitted into the image, which is so much bigger than theirselves (as you can see, they built a stage and staircase around it because the sculpture was too big to simply step into). How they find theirselves in the stomach of the dino, as if they were all eaten by it, but at the same time as if they are trying to eat their way out. I think this is a nice metaphor for the creation of the sculpture: a group of scientists, sitting at a table, talking about a creature that might have existed one time, and fantasizing how it must have looked. During their conversation, when they discover more and more, and agree more and more, the image around them grows. It grows legs, sharp claws, grows further upwards and forms a stomach around the scientists, and the longer they talk the more the animal shuts them in, until they finally give it a name and the Iguanodon closes above them.

Dinner in the Iguanodon Model at the Crystal Palace

Another, perhaps even more beautiful drawing was placed in the same newspaper a week later. It depicts the so called “Iguanodon Dinner”. When the sculptures were nearly finished, they threw a dinner party for all the scientists involved. The dinner was served in the half-finished model of the Iguanodon. They placed a long table in the stomach of this beast, around which the group could sit and eat. I think this is a fantastic image: how the discoverers/authors of this animal all fitted into the image, which is so much bigger than theirselves (as you can see, they built a stage and staircase around it because the sculpture was too big to simply step into). How they find theirselves in the stomach of the dino, as if they were all eaten by it, but at the same time as if they are trying to eat their way out. I think this is a nice metaphor for the creation of the sculpture: a group of scientists, sitting at a table, talking about a creature that might have existed one time, and fantasizing how it must have looked. During their conversation, when they discover more and more, and agree more and more, the image around them grows. It grows legs, sharp claws, grows further upwards and forms a stomach around the scientists, and the longer they talk the more the animal shuts them in, until they finally give it a name and the Iguanodon closes above them.

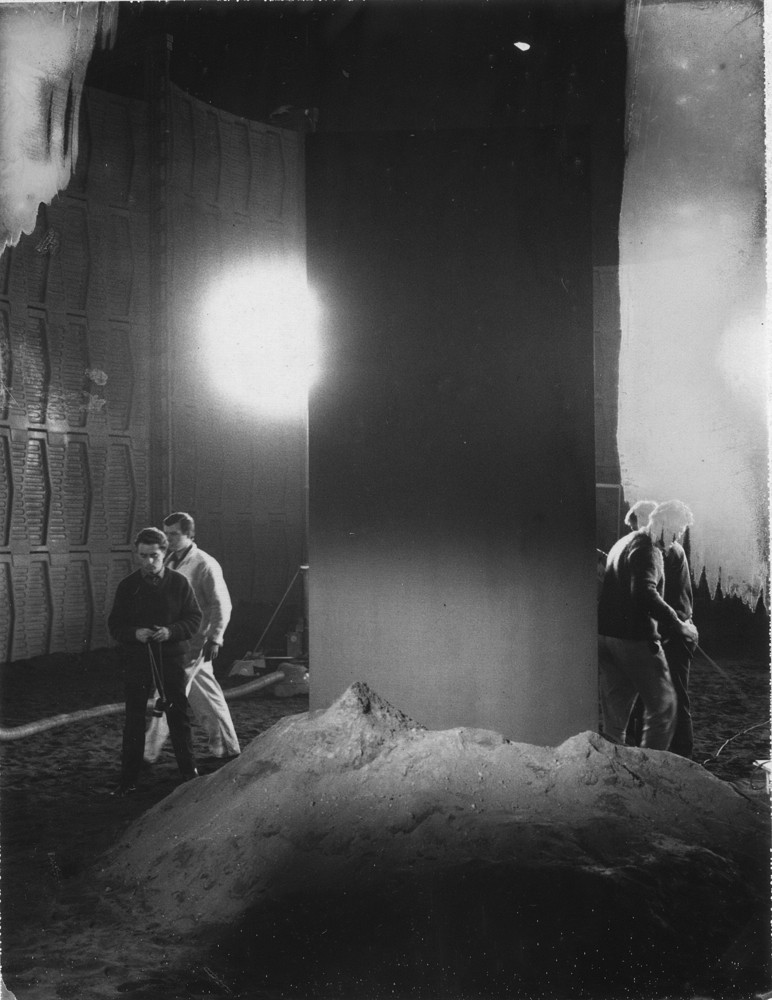

2001: A Space Odyssey

What is interesting about the film 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick, is that the film (in which a space travel to the moon is made) was made before the first human set foot on the moon. For all the scenes that take place on the moon, Kubrick had to completely imagine what it must look like.

A nice detail is that this is often an argument people bring forward in the discussion about whether or not the moon landing actually took place. Because if Stanley Kubrick can make such a realistic depiction of the moon landing, then NASA should easily be able to do the same.

Echo II

Echo II was a balloon-satellite of NASA, which NASA themselves called “The most beautiful object ever launched into Space”.

“Scholar’s Rocks” from the Qing Dinasty

All these objects are found in China, and stem from the time of the Qing Dynasty. A huge quantity of similar objects was found. All of them are weirdly formed, often twisting pieces of natural stone, carefully placed on little wooden supporting bases. The stones are often called “Scholar’s Rocks”, because a lot of scientists collected these, and they placed them on an important place on their desk, or otherwise somewhere else in their working space. It’s not known what the exact reason for this collecting was. The “Scholar’s Rocks” are not manmade, only their bases are. They are all small pieces of wilderness, to be put on a sole and admired at home.

“Chinsekikan”-Museum, Japan

In this Japanese museum a collection of stones that look like human faces are displayed. There are showcases full of different kinds of stones, all of them representing different sorts of faces. I think this museum is a good example of the way we look for ourselves in the unknown, and use our own bodies to measure the wilderness.

Annabelle Binnerts (1995) graduated from Image and Language at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in 2017. For her graduation work she examined the way we relate to immense, unknown spaces. She is fascinated by the ways in which we try to grasp these spaces, how we try to give a human measure to the unmeasurable.