#02: Who wants to live now-forever?

on time-specific and no-time art

The past decade has brought so many “now it does” inventions in (art) technologies. In the beginning, synthetic materials have emerged as life-saviours where surrogate materials were needed. The first plastic, called celluloid, was invented because ivory, used for billiard balls in 19th century America, was almost exterminated. After saving many elephants’ lives, celluloid has led to new media – photography and film started making the history. It was also a replacement for the hard-to-get, expensive material – silk for making parachutes in the Second World War in Germany, so Nylon (polyamide) was invented and used, and later on became one of the most important materials in producing fabrics in the ‘wash and go’ fashion design.

Being solid, permanent, super-effective, frequent, cheap, easy to handle, diverse and good-looking – synthetic materials were predominant in the other half of the 20th century. Up to the 2000s, the only technological lack of synthetic acrylic paint was that it did not stick to any greasy or slippery base. Now it does. Pigments couldn’t reach the absolute colour. In 2014, the absolute black pigment called Vantablack1 was invented in the UK, and it absorbs 99,965% of the light. Now they can.

HOW DOES ART PRACTICE THIS?

With synthetic materials, matter itself started reaching a no-aging/no-changing, non-influential life. In the period of 2000 to 2010 the absolute got real. This synthetic power station has started to boost one important issue: afterlife. In the past sixty to seventy years of active usage of synthetic matter, we have gotten to realise that the absolute isn’t organic!

A synthetic (read: absolute) matter doesn’t have a second-life. It stays. Disturbingly. Plastics are degradable, meaning they break down, some plastics can also be re-used to some point, but are not compostable and do not take part in the life chain. They don’t connect. The paradox is that the most solid matter that we have produced, remains a forever- haunting phantom.

The idea of promptness that synthetic materials have proved has led to fast-to-instant reactions, temporary art toward presentism. The last two decades have some strong points here:

Many sculptors that have been working with traditional materials for decades, have now started experimenting with the idea of temporality and instant deformability, like Croatian artist Ivan Kožarić.

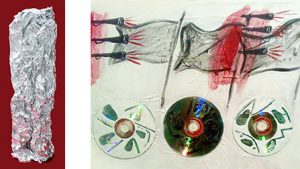

Bosnian and Herzegovinian painter Nusret Pašić paints over music CDs, a poly-propylene plastic, rewriting the data in the present time, witnessing the mere moment.

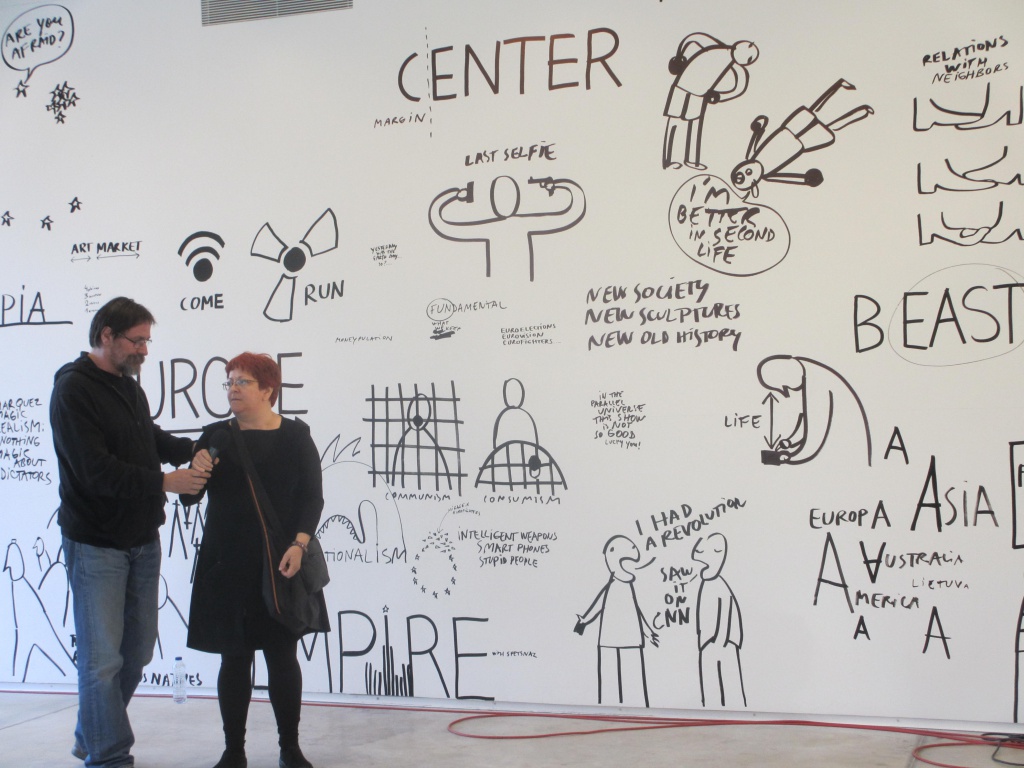

For the past two decades, Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi is known for drawing directly on the walls and window glasses of institutions, often in-situ and whilst the exhibition is ongoing. Drawing cartoons, graffiti and press drawings with non-existing marker-pens, about what is happening in the world at the very moment; he transforms the museum into a database of actuality. He creates time-specific installations.

Austrian artist Erwin Wurm creates his ongoing “One minute sculptures” opus from the mid-90s, where viewers are invited to take part in the artwork for one minute, following the author’s drawing for directions, combining most various objects. Promptness starts calling for randomness (toward scribomania?). Influenced by Wurm, the band Red Hot Chilli Peppers made the video for the song ‘Can’t Stop’ (“To be part of the wave”)

“I liked having the markers and things stuck in my face,” Flea said. “I felt like I was doing something good, like I was earning a living — good, blue-collar work.”

On the other hand, the last decade of the 2nd millennium, faced with the disappointment that the absolute (matter) can’t be ridden of (!), technologies have started re-discovering the potential of the organic. At this point, compostable plastics are being invented for real circular economy (the matter produces energy with no investing substances and with no waste), from natural materials such as cow manure, corn, potato, pines; working on improvements, as we speak.

Dutch Designer Jalila Essaïdi8 uses cow manure for making bio-paper, bio-fabrics and bio-plastics. One of her projects from 2016 is entitled ‘Mestic’ with her BioArt Laboratories, situated in Eindhoven, where she succeeds in using these bio-fabrics in fashion design.

The simple, organic matter that seems to have always been there is recharged. This moment of recharging the great potential of the known matter is turning into no-time or total-time.

Maybe at this point we can once again relate to what Kasim Prohić9, the Bosnian and Herzegovinian philosopher, writes in his book “Figure otvorenih značenja” (1976): “aware of the absolute, live relatively.”

Đenita Kuštrić is a visual artist and fine arts technologist from Mostar, based in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. She is interested in the phenomenon of prosthesis as communication afterness – what contributes reality and how to trigger it. She is an assistant professor at the Art Academy in Sarajevo, teaching Fine Arts Technologies.