#08: How to make a city flat

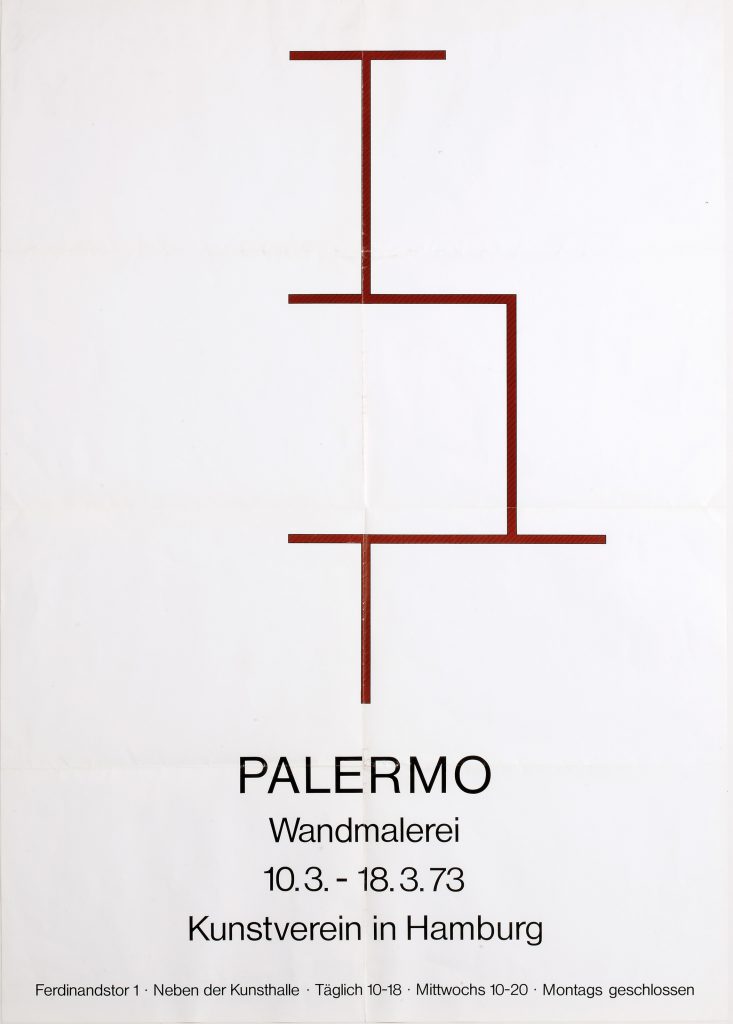

Peter Schwarze was born in Germany in 1943. After his adoption he received the name of Peter Heisterkamp. When he attended art school in Düsseldorf he chose to go by the name of Blinky Palermo. Influenced by artists such as Malevich and Mondrian, he developed his own abstract modernist style that is hard to precisely pinpoint in a specific movement. His work is known as revolutionary because of his use of seaming, materials such as aluminum and commercial fabrics.

Blinky Palermo exhibited his artworks in Hamburg in 1973. He painted the walls and partitions of exhibition room in his own style. In front of his installation he drew the floor plan of exhibition with black chalk. At the end of the exhibition the work was overpainted and, only the drawing of the floor plan remained.

This drawing is now on display in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. It reminded me what I was about to do. In two weeks I wanted to make sense of Hamburg so I could write about the planning culture in my PhD dissertation. Just like Blinky, I wanted to draw a floor plan, so other people could trace back my conception of Hamburg to the streets of the city. The knowledge I gather would become understandable for people that never have been to Hamburg. It’s what scientists do. The philosopher Bruno Latour made this sharp observation about this practice:

Yes, scientists master the world, but only if the world comes to them in the form of two-dimensional, superposable, combinable inscriptions. It has always been the same story, ever since Thales stood at the foot of the Pyramids (Latour, 1999, p29).

So how do I translate this complex, buzzing city into a two-dimensional text? How did I make this city flat?

Day 1

One of the tools I need to make a city flat is a passport. It was really easy to go through all the security checks, but this would have been impossible without my passport. Once I landed I used Google Maps to guide me to my apartment. For a geographer I am very bad in navigating and reading maps. So of course I took the wrong train an ended up at the wrong side of the city.

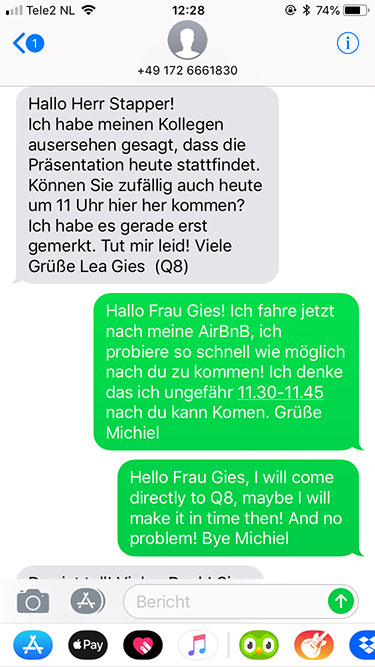

Quite randomly – or was the universe involved – I received a text from someone with whom I had an appointment. She had mistaken the day and she asked if I could do the presentation today at 11.00 o’clock. It was 10.25. But thanks to my mistake I could take a direct train to her organization. My tight planning for the coming two weeks were already changing an hour after arrival. The city did not let herself become flat so easily.

Day 2

When I woke up this morning, I was a bit nervous. I had one meeting planned that was very important for my research and one in which I had to speak German. In Amsterdam, I had taken German lessons and listened to thousands of German podcast, so my understanding of German is fine but speaking is something else. To make a city flat you need to understand its language. When I arrived an hour too early for my important meeting I received a call; I could perhaps postpone the meeting to tomorrow. I did not have a lot of time that day, but because the meeting was important I said yes and hoped that one of my other meetings on that day could be postponed.

The meeting in the evening was with lovely people that explained a lot about their Baugemeinschaft. My German was really bad, and to be honest, I could not understand everything. Learning a language is so complicated. When I walked back through the night of Hamburg I was thinking about how in two days already so many meetings were changed. Maybe it was a sign of the city that I wasn’t the one that could tell what Hamburg is, that she only could tell it herself. I should follow the flow of the city, not try to freeze the city.

Day 3

Today I had three meetings, all at opposite ends of the city. I was again quite nervous, I had a meeting with a person who is of importance for my research. I didn’t know how much she would like the idea of being researched. But she agreed to meet me, after receiving 213 mails from me. Luckily, she was very nice and we had a good conversation. I raced to my next meeting and rang the bell but nobody opened. So I telephoned the person, she said that the door was open and that I needed to climb the stairs. It’s funny how expectations withhold you from directly looking if the door is open.

My last meeting of the day was one of the most insightful conversations I had. I noticed that the person I was talking to was very nervous. I had previously asked if we could speak English and he had said that it was okay, but that he was not good at it. In order to ease his mood I started to ramble about the nice view of his office. He had printed my questions and had already answered them in bullet points. Next to him was a list of words from German to English. His English was actually very good, and at the end he told me that he knew a few Dutch words. However, when he speaks with Dutch people, they never get what he’s saying so he switches to English.

Day 4

This day I finally was not so nervous. After three days of crisscrossing the city and speaking to different people I started to feel more at ease. I started to recognize roads and wasn’t constantly checking Google Maps to navigate myself through the city. I started to notice differences with the city of Amsterdam. Political symbols are way more visible in Hamburg. Stickers with political slogans were everywhere. In many neighborhoods I noticed several squatted buildings. What’s amazing about Hamburg is that the port is very close to the city center. When you ride through the city you will pass various places where you notice the cranes and docks from the port. I started to slowly get a feeling about how this city flows.

Day 5

Today I had a meeting with a politician in a nice café in St. Pauli. The neighborhood of St. Pauli is known for its local and global activism. The streets are painted with texts that call for action against neoliberalism, gentrification and globalization. I saw many tattoo shops, sex shops and bars. The neighborhood is split by the Reeperbahn, the infamous street with its strip clubs and louche bars. A mix of homeless people and tourists walk along both sides of the Reeperbahn; the middle of the Reeperbahn is for cars. The weather is grey, and so are the streets. Locals have told me that during the night St. Pauli is in its best shape. It’s true. Thousands of neon lights illuminate the streets. The atmosphere is exciting. St. Pauli knows how to put on a show at night.

Day 6 & 7

Fritz Kola, the hipster-cola, has its origin in Hamburg. In Amsterdam, many cafes that try to be cool have Fritz Kola. It is used to signal good taste. In Hamburg there is quite a strong lemonade culture, with many different lemonade brands. As a Hamburger once said to me, Fritz-Kola is not particularly cool in Hamburg. On the bottle there is a sign that says: Pfand gehört daneben. It means that you should place your empty bottle beneath the bin.

It shows how intertwined Fritz Kola is with Hamburg. The homeless people of Hamburg gather bottles and get a little bit of money in return when they hand in their bottles. The bottles are than recycled. The municipality of Hamburg installed new trash cans for the bottles a few years ago. This triggered protests in Hamburg, because throwing away your bottle would mean that the homeless couldn’t earn money anymore. Fritz Kola thus decided to support the protests with a sign that encouraged people to not throw away the bottle. It is an interesting symbol of the connectedness between the lemonade culture and the protest culture of Hamburg. It also shows that Hamburg is a city of entrepreneurs and tradesmen. Maybe this bottle is all I need to make the city flat.

Day 8

Geography and history influence the way you think about politics. Today I talked with a Canadian about the social movements of Hamburg. He was part of the scene of Hamburg activists and we talked about the differences between Germany, Canada and The Netherlands. It was the week in which the Dutch people could vote for or against a law that gave security service new rights to violate privacy of citizens. Such a law would have crowded the streets of German cities with protesters, but it only triggered a debate in newspapers and on talk shows in the Netherlands.

Day 9

Today I had to cycle from the eastern part of Hamburg to the western part. It was finally sunny and I was thinking about how great my job was. I was doing this for a living. It made me feel really happy. Hafencity is a former part of the Hamburg port and is now developed into a business- and housing area. It – of course – sparked protests in Hamburg, but on this day it was impressive to ride through the area with its big buildings, the way too expensive Elbphilharmonie and old warehouses. From Hafencity I cycled to the oldest parts of Hamburg. Some old warehouses still remain, but large parts were bombed in the Second World War. From there I arrived in St. Pauli with its many squatted areas and finally I arrived in Altona. Altona was not bombed in the Second World War, it is now one of the most popular areas and it’s quickly gentrifying. The bike ride showed how a city is much like an ecosystem; it grows, adapts and evolves over time. Periods of flourishing are altered by periods of decay.

Day 10

Today I visited a project where they have made contractual agreements about the promoting of cargo-bikes. Cargo-bikes are often the topic of jokes in Amsterdam and connected to stereotypes of white middle-class women. In Hamburg they invested quite some time and money in getting people to use cargo-bikes. And although there are many bicycle lanes in Hamburg and people seem to be really attached to their bikes, I would not say that the city is as bicycle friendly as Amsterdam. Where more and more streets in the Amsterdam become bike-only or bike-preferred, the streets of Hamburg are still very much dominated by cars.

Day 11

Laughing is great. It eases people, it connects people. We communicate through our laughs that the world is weird. That we are all lost in translation. This day I spoke with an important lawyer from the municipality of Hamburg. My German is bad, my knowledge about the law is at best basic. But we laughed a lot during our conversation because we both know that human behaviour is often hilarious.

Day 12

On the final day I had my last meeting. I was tired and very satisfied about how the trip had gone. I spoke with many people and gathered many insights. I had the feeling that Hamburg and I were becoming friends. But Hamburg showed one last time that she was not that willing to be made flat and she resisted me one last time. I had to cycle from my appointment in the south of Hamburg. When I arrived at the bicycle station, I saw that almost all the bicycles were broken. Luckily the app showed that one was still available. I opened it, and then found out that the bicycle was locked to another one. I was becoming frustrated. I had no other choice than walking to another bicycle station, which took 30 minutes. Now I had to hurry to go the airport. It got me thinking. I made this city flat. But my representation of the city was just that. One take on the many, many sides of the city. Once I had drawn my floor plan, Hamburg would change. Like the name of Peter Schwarze changed. Like the walls on which Blinky Palermo had his exhibition in 1973.

Michiel Stapper is born in 1988 and is PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. He has a background in geography and philosophy and is currently working at the sociology department. His research focuses on the democratic legitimacy of contractual agreements in urban development. In his spare time he likes to watch anime, deconstruct Kanye’s tweets and listen to podcasts about the Byzantine Empire.